Validity

In simple terms, validity is about how well we have succeeded in measuring what we set out to measure. Validity can be broken down as follows:

- content validity: are we testing the entire content?

- construct validity: does our exam test for the intended learning objectives?

| ASSESSMENT METHODS | CONTENT VALIDITY | CONSTRUCT VALIDITY |

| MCQ and similar tests | High, as it is possible to cover a very wide range of content | Requires careful consideration of how the questions are asked and which answers are possible. |

| Written invigilated exam without aids | Increases if the questions asked can be about a wide range of the syllabus. | Provided that the learning objectives are a matter of superficial knowledge and awareness of accessible methods, there could be a high level of construct validity. |

| Written invigilated exam with aids | Increases if the questions asked can be about a wide range of the syllabus | Provided that the learning objectives are a matter of knowledge and application of methods, there could be a high level of construct validity. |

| Written paper | Since one question or problem is usually set, high content validity is difficult to achieve. | High, as the period of time allows the student to deal with the subject matter in depth. |

| Portfolio | High, as the portfolio can bring together basically everything that is included in the study programme. | High, if the student’s abilities are to be assessed within a complex, complicated phenomenon. |

| Logs | High, as it continuously asks for reflections on what is going on in the study programme. | High, if the student’s capabilities are to be assessed within a complex, complicated phenomenon. |

| Internship report | Low, as there is no direct documentation of the extent to which the student worked with relevant academic abilities and skill-sets. | Low, as there is no direct documentation of the extent to which the student worked with relevant academic abilities and skill-sets. |

| Oral exam/Viva without preparation | Due to the time factor, it will not be possible to ask a sufficient number of questions to ensure high content validity. | The opportunity to ask individual, follow-up questions allows for high construct validity. |

| Oral exam/Viva with preparation without aids | Depends whether the questions test factual knowledge or generic abilities. | The opportunity to ask individual, follow-up questions allows for high construct validity. |

| Oral exam/Viva with preparation and aids | Relatively high, if questions are formulated in such a way as to test the student’s ability to generate hypotheses, to explain and to apply principles | The opportunity to ask individual, follow-up questions allows for high construct validity. |

| Student presentations | Relatively low, as it only covers a limited area of content. | Low, as the report indirectly documents the degree to which the learning targets have been met. |

| Objective structured clinical exam | Depends on the ratio of station assignments to learning targets, the variation of competency targets involved in the individual station assignments as well as the academic content of the assignments. | Depends on the ratio of station assignments to learning targets, the variation of competency targets involved in the individual station assignments as well as the academic content of the assignments. |

| Practical test | Depends how much of the practical content of the subject can in fact be examined in this way. | Ensured by having clear criteria for the level of complexity of abilities. |

| Active participation | Very high, if the students are able to continually demonstrate their knowledge, skill-sets and abilities. But absolutely worthless if the students achieve a pass mark simply as a result of physical attendance. | Very high, if the students are able to continually demonstrate their knowledge, skill-sets and abilities. But absolutely worthless if the students achieve a pass mark simply as a result of physical attendance. |

| Oral presentation based on synopsis | Usually low, as the synopsis and the student’s presentation usually only deal with a single question out of the academic content. | Relatively high, depending on the requirements for the synopsis and the oral presentation. |

| Written paper with oral defence | Usually low, as a written paper usually only deals with part of the syllabus. However, it is possible to ask detailed questions about the rest of the syllabus in the oral exam. | Relatively high, depending on the types of questions. |

| Portfolio and oral exam | High, as the portfolio element can bring together basically everything that is reviewed in the study programme. | High, if the student’s abilities are to be assessed within a complex, complicated phenomenon. |

| Project exam | Usually low, as projects usually only deals with part of the syllabus. | Relatively high, depending on the report outline. |

More about Validity

In simple terms, validity is about how well we have succeeded in measuring what we set out to measure.

If we probe more deeply into the concept of validity, things become more complex, as the concept is related to the exam results, and not the exam itself. In other words, there are varying degrees of validity; it is not a matter of whether or not the exam is valid. Another aspect of this complexity is that there is more than one dimension to validity – there is depth, and there is breadth.

When speaking of the validity of the exam in terms of breadth, this is content validity – whether the exam tests the entire content. For example, if an exam contains 15 questions, the content validity of the exam is low if all 15 questions are about the same aspect of the many topics embodied in the subject. Similarly, the validity of the exam would be low if, for example, one out of three assignments in an exam was about a sub-topic that covered only 1/10 of the syllabus.

When speaking of the validity of the exam in terms of depth, on the other hand, this is construct validity – whether the exam tests the learning targets to the classificatory level. For example, if an exam is designed as questions with closed answer categories (as in MCQ, for example), its construct validity will be quite low if the learning target for the course was to enable students to cultivate problem-solving skills.

Another consideration in terms of validity that can also be said to point towards depth is predicative validity – in other words, whether the exam results can be used to forecast the student’s capacity to engage with the subject in other contexts, whether in other subjects or in the student’s subsequent working life. Here, considerations of validity address the extent to which this type of exam is capable of predicting whether students will be able to cope with their future work.

Another consideration in terms of validity that can also be said to point towards depth is predicative validity – in other words, whether the exam results can be used to forecast the student’s capacity to engage with the subject in other contexts, whether in other subjects or in the student’s subsequent working life. Here, considerations of validity address the extent to which this type of exam is capable of predicting whether students will be able to cope with their future work.

However, the exam must also be designed to ensure that students are given the opportunity to perform at a level corresponding to their academic level. The exam must also be valid in relation to what students are able to do. Normally, this is dealt with by including sub-tasks of varying difficulty in the exam or by ensuring that the single assignment set is moderately difficult. This should make it possible for students to be assessed according to their own capabilities, whatever their academic level.

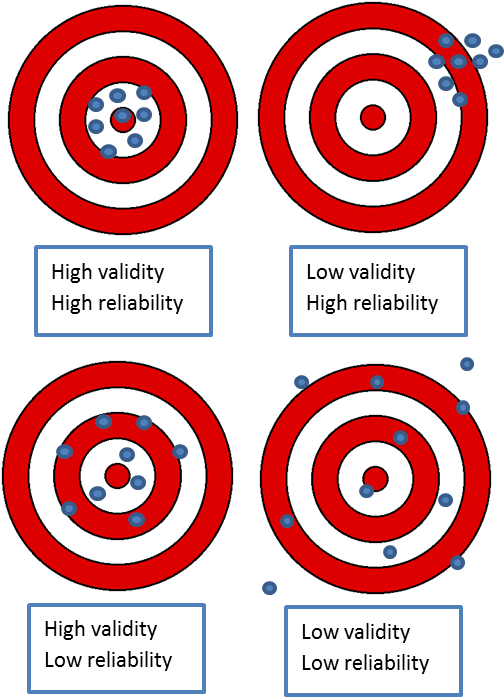

In practice, striking a balance between validity and reliability is often the basis of the negotiated soundness of this type of exam. To the right, there are four scenarios combining high and low validity and reliability respectively. The centre of the target represents the key learning targets, and the “bullets” are the students’ answers. High validity and high reliability are, of course, preferable, and the combination of low validity and low reliability is not worth striving for. However, the two intermediate positions are perhaps the most realistic, and here all we can do is encourage exam planners to be aware of the strengths of the particular type of exam they want, and of where additional questions or combinations of exams could usefully be added.

(The target metaphor is derived from Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.) Wadsworth: Cengage Learning)